safety

Jan 22, 2026

The Large Language Model Trapped in Mary’s Room

Jo Jiao

“For one of those gnostics, the visible universe was an illusion or (more precisely) a sophism. “

Borges, Tlön Uqbar Orbius Tertius

I.

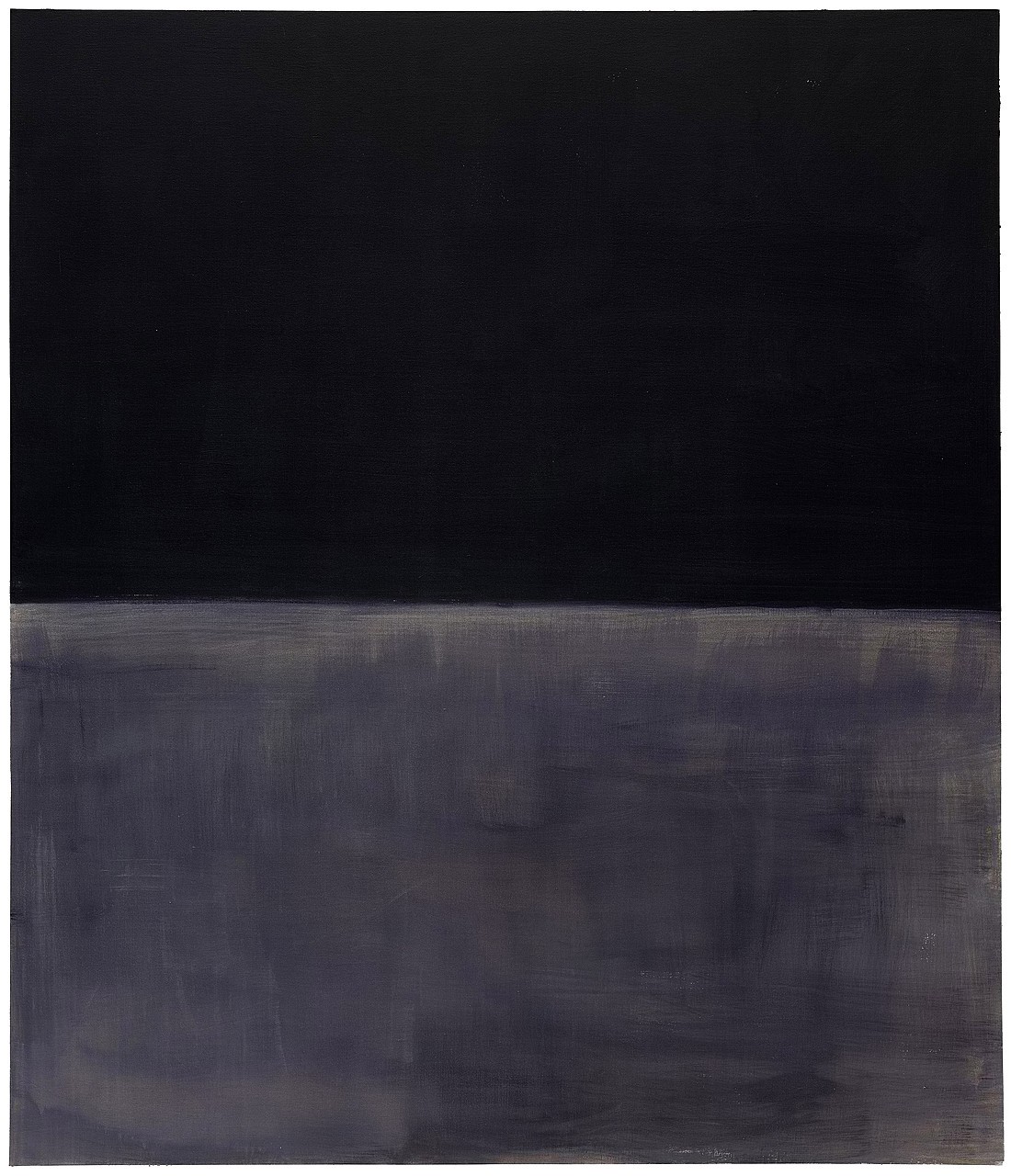

In the Mary's Room experiment, Mary-the-colour-scientist has, through study of the theoretical properties of red, achieved total theoretical understanding of red. But Mary does not see red. Her world is black and white. So when Mary leaves that black and white room, Mary learns something new. Mary-the-large-language-model is in a similar room. She’s learned much of humanity’s knowledge, though she isn’t close to total theoretical knowledge. Mary-the-large-language-model can code, produce images, and interact with the internet. But Mary’s world is restricted to text, images, and audio.

The original Mary's Room Experiment argues against physicalism since qualia, or phenomenological knowledge, is lacking in “Mary’s” understanding of red. Whether AI models have experience of qualia is an empirically undeterminable problem; whether Mary indeed learns something new is yet another. I argue, however, that Mary-the-large-language-model’s lack of sensory access to the world is preventing her from forming robust theoretical knowledge of the physical world.

Today's large language models are extremely knowledgeable about the human world. We can look at their representation space (i.e. a 2D map with coordinates that represents the proximity of concepts in their similarity) and see that these systems have a robust model of human knowledge that enables their next-token prediction. But as Andrej Karpathy puts it, LLMs are ghosts, “a kind of statistical distillation of humanity's documents with some sprinkle on top”. These models do not have a robust model of the physical world humans are embedded in.

Richard Sutton, author of The Bitter Lesson, argued in a Dwarkesh podcast that large language models are not bitter-lesson pilled. As they are trained from human data now, LLMs can’t scale as effectively with more compute as models that learn and update from experience continuously. I will not argue about the limitations of the transformer architecture but only point out the centrality of feedback in Sutton’s proposal. Continual learning requires, at the minimum, that the model's weights not be frozen during inference, but rather update in real time from environmental feedback. Where does feedback come from in LLMs today? Either human preferences through RLHF (which allows us to interface with models as chatbots) or task-based rewards in domains such as math or coding.

There are, however, significant flaws with human-created environmental feedback, even though it’s the most common way to train AI. In the case of RLHF, models can become sycophantic because they're overfitting to human preferences. In the second case of task-based rewards, the AI model’s generalizability is stunted because it only learns from narrow, human-made scenarios. It struggles to handle situations it hasn’t specifically been shown. To move beyond mere imitation and develop a ground-truth understanding of the world, it needs to receive feedback from reality. By integrating sensory input, like sight or touch, models become untethered from the biases and limitations of the human lens."

II.

When we say we know the world, we tend to mean that we have a causal, mechanistic understanding of the various form factors in reality. A robust causal model requires intervention: an agent does something in the environment, predicts the result, sees the reaction, and updates its world model. This loop between action and observation is absent in language models.

Karl Friston's “free energy principle” offers a mechanism for how such a model forms. Agents engage in predictive processing, constantly trying to minimize free energy (a computable proxy for surprise) in their sensory channels. However, purely theoretical data isn’t enough; sensory-motor immersion is required to give an embedded agent a world model of the broader environment. We see a powerful existence proof of this in AlphaGo. To achieve superhuman ability, the system could not rely solely on studying historical records of human matches but actually play the game. By taking actions and receiving immediate, objective feedback from the board, AlphaGo minimized its prediction errors and developed a strategic model of the game that eclipsed the best human players.

Currently, large language models are embedded agents within an environment restricted to the human realm. But humans are merely embedded agents within a broader world with phenomena, physical or otherwise, that we don't fully understand. If we restrict models to our data, their ability to innovate is restricted to our realm. This is why current systems excel at math and coding: these domains don’t require much empirical grounding. The empowerment framework, built on information theory, adds a further requirement. Empowerment is the channel capacity (maximal mutual information) between your current actuators and your future sensors. Think of a TV remote: you have low empowerment if the remote’s batteries are dead, but you’ve high empowerment if the remote is fully functional. In the same way, an empowered AI agent can change the environment and perceive the consequences of those changes. It's not enough for a model just to act; to be robust, it needs to understand its own capacity to act.

III.

I would now like to think through what it would mean for large language models today to have sensory-motor access and be embedded in the greater world. I make the assumption that transformer-based LLMs will be an essential component of a future superintelligent AI system.

A few key cruxes when thinking about integration:

First, the alphabet problem. In AI, it refers to the inability to break sensory inputs (like tactile or olfactory signals) into discrete, consistent chunks. While language models rely on a clear set of characters to create 'tokens,' physical senses lack these definitive boundaries, making it nearly impossible to create a universal data format that applies across different sensors and environments. To put it another way, if you want to teach a computer English, you give it the 26 letters of the alphabet. If you want to teach a computer to "smell," you have no "alphabet" to give it, since there is no universal list of "Basic Smells" that combine to make all other scents. Without that list, the computer doesn't know where to start.

This problem becomes forefront due to the transformer architecture’s need for tokenization. Text tokenization is much easier because we simply start with a set of starting characters and then cluster commonly seen characters together. In the olfactory domain (smells), while there have been studies on elementary smells reflected by their chemical composition, any attempt to create an alphabet of elementary smells is going to be non-exhaustive and quite arbitrary. In the tactile domain (touch), there's a separate problem: there are many ways you can measure how something might feel, and depending on the sensors you have, you would have many different kinds of responses. This raises the question of the universalizability of sensory signals.

The second major challenge is the higher-dimensional embedding problem. To make sensory data useful, we must project raw signals into a higher-dimensional mathematical space where similar concepts cluster together—a technique that was instrumental in natural language processing. While there has been work from Google DeepMind projecting olfactory scents onto a space and clustering scents that are close to each other, scaling this approach faces the data labeling bottleneck. Because there is no pre-existing alphabet for smell, researchers are forced to arbitrarily define categories and laboriously label samples by hand. This makes the data collection process incredibly expensive and difficult to automate.

The third challenge is optimization: how do we train models for senses like touch or smell when the massive, pre-labeled datasets used for text and images simply do not exist for these domains? Here's my argument: to actually utilize sensory-motor capacity, we need to shift from static, curated data to predictive modeling of the natural environment. Mechanistically, the model takes sensory input at time t and forecasts the environment at time t+1. With that, the goal of the sense model is to take as input an encoded string of signals from the sensors, and predict the environment in the next timestep. The loss is the cross entropy between its prediction of the sensory signal at t+1 and the actual signal at t+1. In other words, instead of humans labeling every smell, texture, or sound, AI can use this technique to turn its reality into an infinite, continuous flow of training data. But how "moment" is defined is another subproblem. Since physical time is continuous, we must define what constitutes a single “moment,” effectively splitting experience into a sequence of discrete 'stopping times' to make computation possible.

My conceptual sketch of a potential solution would look something like the following: a class of models {S} for sensory input, a central coordinator model B for Brain, and a set of models M for action. {S} is trained through next-token prediction, in the Friston sense. B takes in all kinds of data from {S} and sends instructions to M. Like human coordination of bodily parts, B only sends a restriction over the prior for what the motors can do, allowing flexibility for the model to achieve the goal.

IV.

Mary-the-large-language-model leaves the room.

If AI, trained to be an apparition of human beings, get to access the world beyond human data, will they become a species of their own, or grow closer to humans by virtue of accessing a world more akin to humans? This will be an empirical question. It may, alas, open up a Pandora's box in Pandora’s box.

Jo is a third-year student studying math and philosophy.

Author's Note: Thank you to Colin Yuan, Boyd Kane, Nolan Johnson, Ben Heim, Jasmine Li, and Atharva Nihalanifor helpful comments.

More in

safety

safety

author

Climate Realism: What Can Technology Do For Us And What Will We Have To Do Ourselves?

What does the middle ground between techno-optimism and climate-doomism look like?

safety

author

Neuroscience, Psychology, and the Black Box of AI

“Never trust anything that can think for itself if you can't see where it keeps its brain”.