culture

Jan 22, 2026

The Meaning of Progress: A Founder's Manifesto

Max Ruskowski

The conversation around a post-AGI world has been dominated by a single idea: universal basic income. The premise is simple. If machines can do most work better and faster than humans, people will need income support to survive. But this is a left-brained worldview that is viewing AI-driven unemployment in purely mechanistic, managerial terms; this vision of the future misses something essential about human dignity and the nature of value itself: people do not simply want to consume, they want to create, contribute, and own a piece of what they bring into the world. Instead of a universal basic income (UBI), we should be thinking about a universal small business (USB).

In this vision, every individual operates as a micro-enterprise, with AGI as their business partner. Instead of waiting for a check from the state, people use AGI to spin up new ventures that reflect their skills, passions, and perspectives. AI agents handle the operational burden, including marketing, logistics, customer service, etc. The implication is that every person can now scale ideas to a global market with the same operational ease as today's largest corporations. The power of USB is that it turns everyone into an owner. It expands the base of value creation rather than concentrating it in the hands of a few corporations or redistributing it through taxation. A baker, teacher, craftsperson, or designer can all have AGI-powered businesses that reach customers worldwide. Instead of subsidizing idleness, society cultivates widespread entrepreneurship.

Such a system would also make the economy more resilient. If millions of micro-enterprises are constantly innovating, adapting, and serving niches, the economic system cannot collapse as easily as one built around a handful of mega-corporations. The result is a fractal economy, full of diversity and flexibility. Failures in one sector are balanced by opportunities in another, and stability comes from the sheer breadth of participation. This must be assumed with the assumption that AGI reduces the sort of operational inefficiency that comes with businesses that are not operating at scale. Meaning, AGI, through some hyper-efficient mode of production, can make sure that costs are low even though micro-businesses have no economies of scale.

My case against UBI is that the highest form of work has always been more than survival. It is a way to build identity, express creativity, do social good, and feel connected to something larger. UBI risks reducing humans to dopamine-driven consumers in a machine-run economy, stripping away agency and hollowing out meaning. Even the current trend of society shows that people, when given sufficient economic surplus and left to their own devices, don't always turn toward creativity and innovation—it more closely resembles the world where people make a living to buy the things they like and support their pleasures. In his discussions on the “useless class” (people rendered unemployable by AI), Yuval Noah Harari has explicitly warned that such a class will have to be kept “pacified” with distractions like entertainment, VR games, and even drugs. USB reverses these potential UBI effects. In particular, USB satisfies the psychological stimulation from working with the dignity of production. Critics might contend that not everyone wants to be an entrepreneur. That is true in the current world, where entrepreneurship means high risk and financial insecurity. But in the machine-run world where USB dominates, a job is the highest risk of all because it risks being automated by AI. Therefore, the market for USB is designed to put pressure on people to produce while lowering the difficulty threshold of running a business with AI. Much like how critics argued that being literate wasn’t required because it was reserved for priests and scribes in the 1400s, literacy is a requirement to participate in society today. Similarly, I believe that running one’s own business will become the default way to participate in a post-AGI society.

What Defines a Successful Business in the Age of AGI

While the tools that AGI brings for business owners levels the playing field, there will be businesses in the future that do better than others. The competitive pressure will be mainly defined in terms of companies’ atomic stock, physical progress, regulatory hacking, and improving reality.

In standard microeconomic theory, value accrues to the scarce resource rather than the commoditized input. As AGI drives the marginal cost of cognitive labor and digital production toward zero, the economic landscape undergoes a fundamental inversion. We are witnessing the end of the era defined by Marc Andreessen’s famous dictum that "software is eating the world." In a saturated digital environment, the physical world eats software. Also from microeconomics is the phenomenon that the quantity demanded of a complementary product rises as the price of its pair falls. When intelligence becomes abundant and cheap, its complementary goods, such as physical assets, land, raw materials, and energy, will be demanded in greater quantities. This suggests that future market dominance will belong to firms that control "atomic stock." These are companies possessing tangible infrastructure that AGI can optimize but cannot digitally replicate. The competitive advantage shifts from those who can generate code to those who own the factories, lithium reserves, and logistics networks required to execute that code. The digital realm serves merely as the control layer for a value chain that is ruthlessly physical.

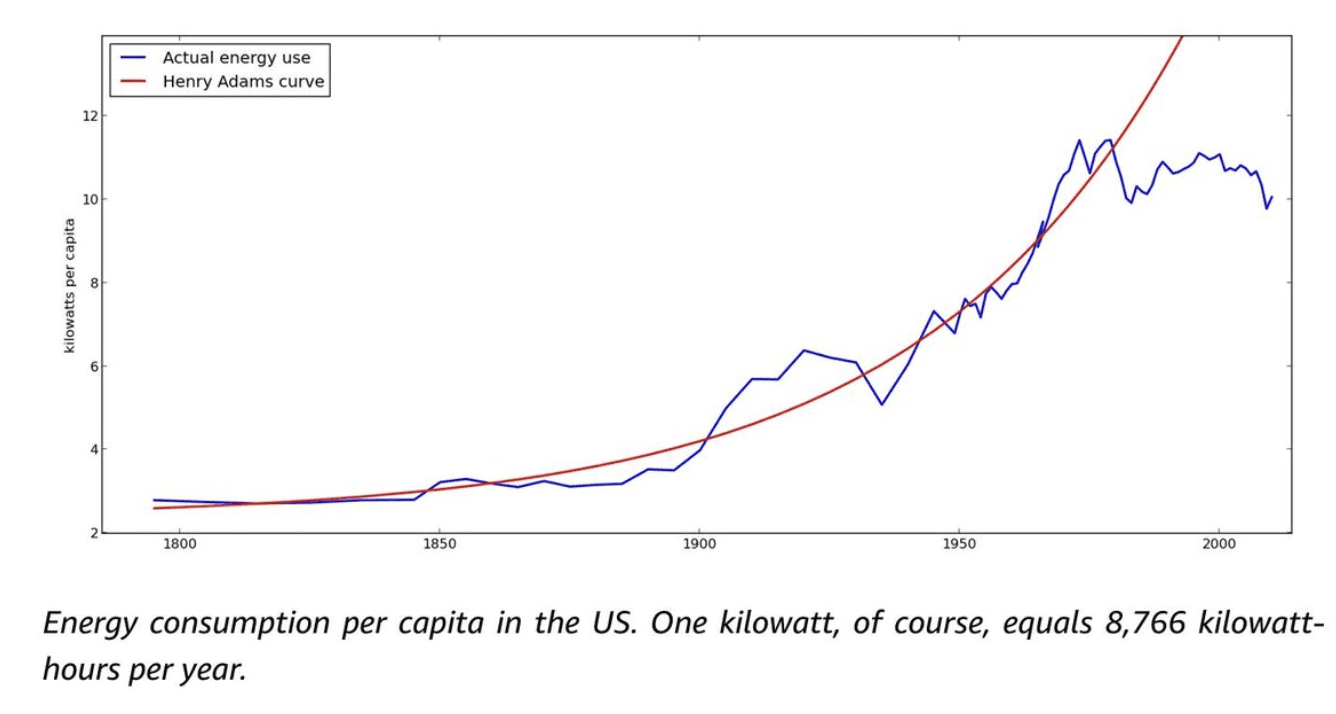

The emphasis on improving our physical world comes from the prevailing economic stagnation of the last fifty years that stemmed from a deceleration in material innovation. This is often characterized by Robert Gordon in The Rise and Fall of American Growth: while the information sector flourished, the manipulation of energy and matter stagnated. J. Storrs Hall, in his analysis of the "Henry Adams Curve," demonstrates that historical trends in energy consumption and physical engineering flatlined starting in the 1970s. This deviation suggests that the low-hanging fruit of purely digital innovation has been harvested. The most successful post-AGI ventures will likely be those that utilize machine intelligence to force a return to the Henry Adams trendline. By applying AGI to complex simulations of fluid dynamics, nuclear physics, and materials science, startups can overcome the engineering bottlenecks that stalled the physical future. The competitive pressure acts as a filter. It selects for organizations capable of translating algorithmic insights into high-energy, high-complexity manufacturing and infrastructure. The market will reward the resumption of tangible growth in the physical world over the further optimization of the digital world.

The bitter truth forcing us to put emphasis back on our reality stems from the fact that modern humans cannot survive without four basic materials: cement, steel, plastics, and ammonia. In Vaclav Smil’s own words, “The world now produces annually about 4.5 billion tons of cement, 1.8 billion tons of steel, nearly 400 million tons of plastics, and 180 million tons of ammonia. But it is ammonia that deserves the top position as our most important material: its synthesis is the basis of all nitrogen fertilizers, and without their applications it would be impossible to feed, at current levels, nearly half of today’s nearly 8 billion people.”

This shift represents a rejection of the simulation in favor of the material. As digital content becomes infinite and therefore valueless, the premium on authentic physical experiences increases. Ventures that apply intelligence to reduce the cost of housing, purify the air supply, or accelerate transportation speeds address the foundational layers of Maslow’s Hierarchy. The market mechanism will increasingly penalize companies that offer mere digital distractions while rewarding those that deliver measurable improvements to the biological reality of the human condition. The next trillion-dollar companies will arguably look less like social networks and more like the industrial titans of the early 20th century, but re-engineered for the 21st.

This brings us back to the question of government governance of a post-AGI economy. USB does not mean there will be no role for governments or large organizations. Infrastructure, energy, healthcare, and heavy industry will still require coordination at scale. But for most of the service economy, creative economy, and much of the cultural economy, the natural shape will be small, individual businesses powered by AI. Governments can support this transition not by handing out stipends, but by ensuring access to AGI tools, fair marketplaces, and basic protections.

This vision demands a radical architectural shift in governance, far exceeding the passive bureaucracy of simple cash transfer programs. To achieve a USB economy, the government must transition from a provider of welfare to a guarantor of cognitive sovereignty in some shape or form. The defining political struggle of this era is to ensure that access to AGI is guaranteed for people’s economic citizenship, as models with varying levels of intelligence priced differently arguably could lead to a new discriminatory practice that favors the wealthy members of society. Therefore, the essential government intervention is to enforce the democratization of the tools themselves, in the sense that we need to steer AI toward “machine-usefulness” rather than “machine-replacement,” in the idea of MIT Economist Daron Acemoglu. This requires aggressive antitrust action, the establishment of public compute infrastructure, and open-source mandates designed to ensure that the infinite leverage of AGI is placed directly into the hands of the individual. Only by treating high-level machine intelligence as a public right can we prevent a feudalism of the future and empower a society of producers.

Modern society is rich in knowledge but poor in meaning. As Richard Saul Wurman famously observed, 'A weekday edition of The New York Times contains more information than the average person was likely to come across in a lifetime in seventeenth-century England.' Yet, this exponential growth in data has coincided with a catastrophic vacuum of purpose. We see this in the rising 'Deaths of Despair' documented by economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton, where mortality rates from suicide, drug overdose, and alcoholism have surged alongside material abundance. This divergence proves that humans cannot survive on consumption alone, no matter how efficient the algorithm. We are born to create. The transition to a USB economy is a way to ensure that in a world drowning in information, we finally give people the tools to build a raft of meaning.

Max is a third-year student studying cognitive science and economics.

(This article was edited by Colin Yuan)

More in

culture

culture

author

AI And The End of Authentic Human Lives

If a machine tells you how to live, are you still living authentically?

culture

author

The Political Brawl Within the Republican Party Over AI Policy

It’s a mistake to think that the contemporary Republican Party adheres to an ideology, and on AI, they each want something different.